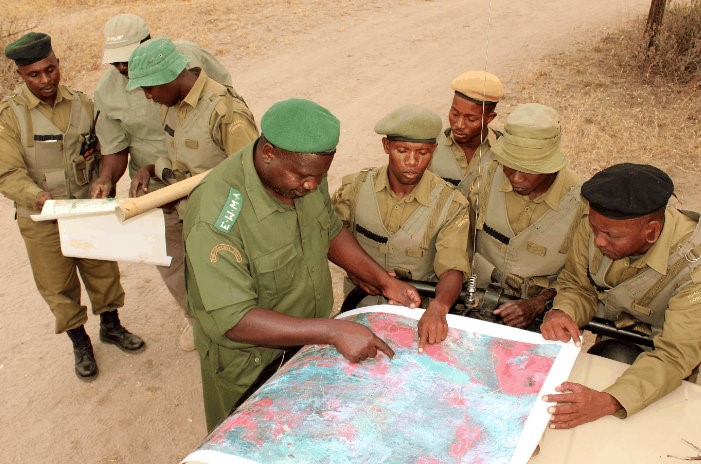

Conservancies best practices participants at AWF Nairobi, Kenya. Photo Credit: Peter Chira /AWF

Africa’s ecosystems, with immense benefits to current and future generations, are at serious risk due to human activities and habitat loss. The Africa Biodiversity Collaborative Group (ABCG) works to conserve biodiversity and natural resources in balance with sustained human livelihoods, and one of the ways we accomplish this is through collaboration and information sharing across conservancies and its African partners.

Therefore, we are excited to announce that one of our members, the Africa Wildlife Foundation (AWF), has published a volume, African Conservancies Volume Towards Best Practices, on best practices among conservancies across the African continent, as the result of a workshop held on April 20, 2016 in Nairobi Kenya. At the workshop, at which ABCG was present, individuals from various NGOs, government agencies, the private sector, and over 10 different countries discussed best practices in conservation across the continent. To read more about the workshop, click here.

“Today is not about the ‘why’ of conservancies, we all agree on the ‘why’, we all know the rate of biodiversity loss, today is about the ‘how’. How do we ensure the conservancies across Africa are sustainable?” remarked Kathleen H. Fitzgerald, Vice President of Land Protection, AWF.

Despite the varying differences among conservancies, there are commonalities among findings of best practices that are cross-cutting. Presented here are analyses of best practices that can be replicated across country contexts.

While there is seldom one method for conservancy establishment, conservancy practitioners can learn from each other and adapt ideas to local contexts. Five factors have been shown to lead to success among conservancies:

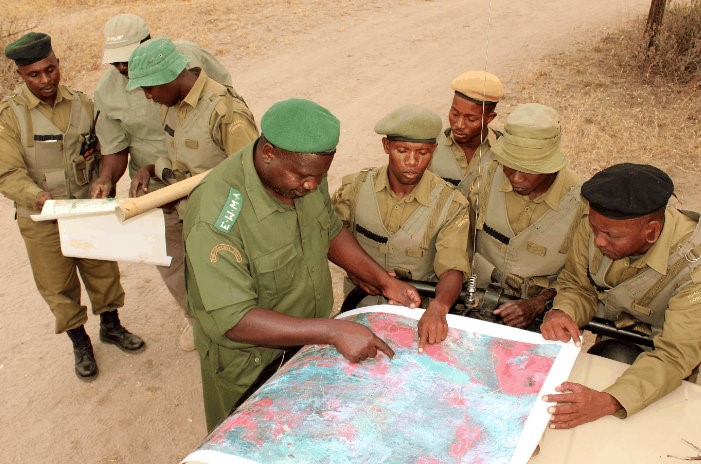

Photo by AWF.

First, a national policy framework (1) is usually in place to support the conservancy. Within a country’s legal system, a system of legal instruments and operational tools is often in place to regulate conservation. Policies not only lay out the principal legislation supporting conservation, but also serve as a convergence among differing views by a wide array of actors (i.e. end users, governments, and the private sector). Within that realm, sound policies and effective laws can be essential to preserve local ecosystems and guide land tenure and resource allocation, which are key factors in creating conservancies. Despite this, there are plenty of communities that have thrived without a policy framework, and instead promoted a grassroots level experimental initiative.

In addition, good governance (2) of conservancies requires transparency and accountability to be successful. Governance is how a community or group organizes itself to make decisions or achieve a goal. Good governance is crucial to successful conservation projects and goals because it leads to high community participation, better leadership, and ultimately an increase trust and support for the conservancy. Governance structures work best when developed by the community under guidance from conservation actors.

Although economic viability (3) is important, it does not need to be the main overarching criterion for success. Some conservancies make up for a lack of economic potential with other gains, such as technical, social, and institutional factors. There are several examples where social and environmental factors are very strong but economic gains are low. Thus, the viability of a conservancy depends on multiple factors, not just economic viability.

Although not all conservancies can directly provide economic gain, some provide social services, such as security, infrastructure, amenities, and livestock management- which are often mandated by the government. Therefore, opportunities can present itself to receive government funding for such services. Lastly, communities need to assume a certain level of risk and bring something to the project, to create the desire to see the conservancy succeed.

Photo by AWF.

Often a conservancy’s success depends on the relationship between humans and each other and the environment in which they live. In other words, the complex social, political, and cultural factors need to be considered to properly manage a conservancy. Considering the socio-political context (4) of a conservancy aids in better understanding human-related sources of ecological stress as well as characteristics and values of stakeholders and its effect on the conservancy.

Lastly, a discussion was held on whether a conservancy can maintain ecological viability (5) in the long term despite the many threats it faces. For ecological viability to be attainable, it is crucial that long term viability is ensured through using simple ecological monitoring systems, integrating solutions based around existing livestock and emerging threats, and cooperating and working collectively with state and local authorities. Community involvement in monitoring is also important, but it needs to be more simplified.

Twelve case studies in seven countries were discussed in this report, including one by the Northern Rangelands Trust in Kenya. In ABCG’s first programmatic phase (2012-2015) as part of its Emerging Issues small grants program, ABCG collaborated with NRT to address global climate change through grazing management and carbon sequestration in community conservancies of Northern Kenya.

To read the full report (including case studies), download the report here.