Conservancies are evidently as vital as a protected areas system in ensuring wildlife habitat integrity and improved livelihoods for stakeholder communities, supporting the case for conservancy development. The characteristics and the approaches taken towards successful conservancies—the ‘how’—forms the rational for this workshop.

As conservation practitioners, land owners and land managers, how do we ensure conservancies in Africa are viable? This is the fundamental question posed by Kathleen Fitzgerald, Vice President for Conservation Strategy, and the lead facilitator of Africa Wildlife Foundation’s (AWF) workshop entitled Best practices towards development of sustainable conservancies in Africa, held in Nairobi, Kenya on 21st April, 2016.

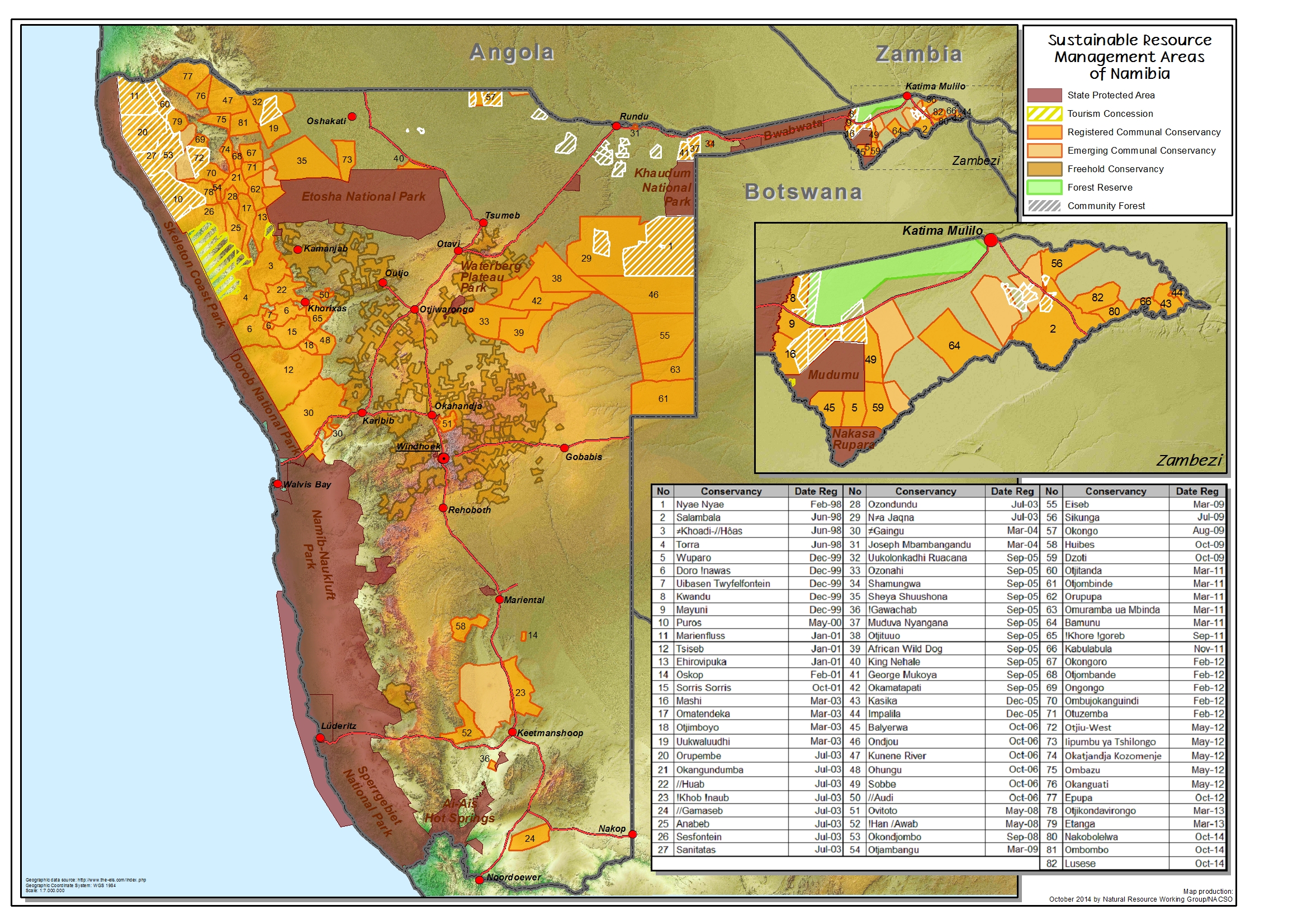

The meeting included participants form across Africa and featuring ten countries include South Africa, Botswana, Namibia, Zimbabwe, Zambia, Mozambique, Tanzania, Uganda, Ethiopia and Kenya. After formal introductions including opening remarks by AWF’s new President, Kaddu Sebunya, Alistair Pole, Director of Land Conservation, set the stage with a discussion on the raft of conservancy models in practice across Africa.

Conservancy models can be categorized broadly into three groups: (1) community, or communally-based, (2) government entity (reserve-like), and (3) private (sanctuary-like). All involve some contractual agreement to form a legal entity, with a board (of Trustees, Directors, etc.), but beyond that, other aspects including land use and management planning varied remarkably.

Five principles of conservancy structure were discussed by experienced field professionals, including:

- Policy Frameworks

- Ecological viability

- Economic viability

- Socio-political

- Governance

POLICY FRAMEWORKS:

Discussions revolved around the question on whether a policy framework—national or sub-national—was a pre-requisite for the development of successful conservancies. For countries such as Kenya, South Africa and others, communal conservancies have developed largely without a national policy framework, and thus pioneered the initiative at a grassroots level. Others such as Zimbabwe, Tanzania and Mozambique, have had government frameworks and legislative instruments guiding their development and characteristics. The issue of whether energy should be spent on lobbying government agencies for a policy framework, or taking the grassroots, experimental path to piloting a conservancy program, remains ambiguous as models have thrived within a solid framework, and some without. However, where possible, allowing for piloting and then following with policy makes most sense, as the policy can reflect actual testing and trialing, like in Kenya.

Timing is key: If there is appetite or political will for a conservancy approach then land owners ought to seize the window of opportunity to innovate. This includes strategic targets such as poverty alleviation in rural areas and mainstreaming conservancy adoption as a national development strategy.

Showing initiative and innovation on the ground can win a conservancy program substantial support from government. In the case of Kenya, conservancies are arguably supporting a government mandate to protect and promote a national asset, thus it was argued a framework was needed to guide and ensure long term presence of conservancies.A sound mission from conservancies must be developed and outcomes communicated to show their public contribution, especially towards social benefits (e.g. employment, security, bursaries) and environmental benefits (enhanced ecosystem services, heterogeneity) bestowed to the larger community, lest the conservancies risk losing their tax exemption.

Much work remains to be done to harmonize different and sometimes competing government departments that may claim jurisdiction and oversight of conservancies. Reconciling the role of relevant government sectors remains a challenge in many countries, particularly Tanzania that has a complex land and user right structure. One suggestion was to advocate for a community-level integrated structure where government ministries and departments can coordinate efficiently.

Large scale agriculture, lack of clear land tenure and extractive industries; are substantial threats to the conservancy model, issues that ABCG has addressed in past and current projects. Due to the high economic returns of such sectors, governments often trump private and communal rights holders “for the greater good”. One solution is to lobby for the bundling of land tenure and resource rights and afford landholders further security in their land; an issue that ABCG is currently tackling cooperatively between several members.

Further questions explored include:

What Conservancy Aspects should be regulated by policy, or what regulations ought to be legislated for conservancies?

- Include checks and balances for community accountability and transparency.

- Regulate wildlife user rights appropriately, such as quotas and off-take.

- Get government to intervene when there is abuse at the conservancy level, above and beyond self-governance and self-policing.

- Government should support resource stewardship on private and communal conservancies in the national interest; similarly, ecological services should be safeguarded.

- Standards and ethics on game cropping/hunting/offtake should be established.

ECOLOGICAL VIABILITY

The overarching concern for ecological viability is ensuring the long-term viability of conservancies to support the functionality of species diversity, population sizes and communities of species in a changing world (human population dynamics, economic activity, climate change).

Key questions include:

- Does exclusionary zoning work, or is it about integrating multiple land uses for viable economic base?

- Climate change factor: How do we incorporate and mainstream into conservancy programming?

- Ecological monitoring and adaptive management: How much monitoring is enough, and what tools are appropriate? Can you engage communities effectively in ecological monitoring?

A primary stressor is fragmentation affecting ecological connectivity, largely driven by human activities. Land policies are biased towards artificial systems resulting in arbitrary boundaries as far as ecosystems are concerned, to the detriment of natural processes such as wildlife migration.

Conservancies are shown to mitigate, even enhance biodiversity in their areas. This often benefits adjacent national level protected area systems, but proper mechanisms need to be in place to sustain conservancy co-benefits, such as a payment for conservation services (subsidization). A national policy framework should consider the role that conservancies play in maintaining heterogeneity and biomass production.

ECONOMIC VIABILITY

Conservancies should assume a business approach to operations much like a startup corporate venture. They should seek expert counseling on securing financing; have good transparency and accountability; be able to cover operating costs, generate reasonable returns and sustain effective production; integrate their business model into the broader economic framework of the locality, nationality and even region; and have flexibility in adapting to the vagaries of the economic environment.

Conservancies are arguably more about securing local assets from misguided development or over-investment, rather than for tourism or wildlife sanctuaries. Such an approach facilitates a conservancy to diversify its livelihood and include conservation enterprise, once their collective and basic human needs are met. For example, conservancies in northern Kenya formed primarily for community security against inter-tribal conflict, to mention but one example before a slew of other opportunities were realized.

Land uses particularly agriculture and settlement are major competitive threats to the conservancy model. One answer is the creation of conservation cooperatives between trusts and conservancies, much like an umbrella organization, to combine resources and leverage economies of scale, making it feasible to address such challenges. Otherwise subdivision remains an expensive options that individuals seek as a fail-safe solution to livelihood security and receipt of direct benefits (stopping elite capture), much to the long-term detriment of longer-term and broader scale opportunities.

The Tourism sector including travel agents and tour operators needs to be enlightened on the benefit of including conservancies in their tour circuits. Without significant tourism revenues, wildlife in national parks that ventures to conservancies are at risk from a source and sink situation.

Communities with conservancies have to diversify their business plans and not be entirely dependent on tourism. This will add resilience against such a fickle industry, such as well-branded export products to the same tourist markets.

On the issue of funding sources, conservancies need to push for a paradigm shift that sees aid being applied holistically. Communities generally do not segregate their livelihood development by health, energy, land, education, etc. Thus, funding should be sustained on a landscape-viable scale, both spatially, temporally, and multi-sectoral, to reflect the realities that targeted communities exist under.

SOCIO-POLITICAL VIABILITY

Top threats:

- Ownership or lack of strong land tenure rights and resource rights framework.

- Inclusivity in the political process at the national and sub-national level.

GOVERNANCE

In northern Kenya, the conservancies of the Northern Rangelands Trust are managed by communities, not private institutions, with elected boards and a management structure. They have instituted a democratic decision-making process and legitimate representation, and enhanced inclusivity. These principles help build social cohesion that promotes the achievement of conservancy objectives. A governance index is a helpful decision support tool to employ in objectively measuring the robustness of conservancy governance. The matrix may include community communications, conservancy satisfaction, board trust, etc. to name but a few parameters.

In addition, customary or traditional governance and authority needs to be integrated, including direct involvement in approval of Board elections and membership.

Governance can be affected by a strong inner strength and identity, such as: (1) Tapping into social capital and social ties in the community; and (2) Leaving room for self-determination (light touch facilitation by external agents). This helps balance a sense of internal purpose with external obligations of running a bona-fide conservancy.

Overall, the workshop was an intellectual and practical discourse. Panelists and participants shared their experiences and views on the approaches they were familiar with, while deliberating on new ideas posed. Community conservation is undoubtedly a practical approach of addressing the needs of biodiversity conservation goals and local development in a viable manner, often in areas where mutual exclusivity of either one would have disadvantageous outcomes for the communities and larger society alike. This is evident by the variety of approaches, and sheer number and growth of conservancies across many regions in Africa.

The workshop confirmed important take-home messages in each of the themes explored. Policy-wise, conservancies benefit hugely from an organized policy framework that secures their land ownership, resource and/or tenure rights; or a combination of these. Ecologically, conservancies are shown to increase the overall resilience of an ecosystem, thus providing a positive feedback to human communities as beneficiaries of enhanced ecosystem services, nature-based enterprises, and corollary multiple benefits. Economically, conservancies are best off when planned and implemented like a well-oiled corporation, with transparency, accountability, diversity and innovative management as pillars of profitable operations. Inclusivity and democratic principles must be incorporated into the governance structure to foster social cohesion at the community level, and integrity beyond.

Add a Comment