Nelson is a senior community development officer responsible for implementing initiatives in sustainable livelihoods programs, conservation and infrastructure projects such as community conservancies and clean energy technologies. But Nelson is witnessing growing pressure in his rural, savanna woodland landscape from seemingly every conceivable interest both afoot and afar. Local pastoralists are stocking ever more head of cattle in an attempt to buffer their livelihoods against the increasingly unpredictable weather patterns. Lions and elephants seem to emulate the vicissitudes of the weather and ‘wander’ onto farming settlements in search of a meal. A newly discovered oil field by a foreign prospecting company has gotten wealthy urban investors buying off land in the middle of nowhere from desperate pastoral communities. While Nelson is fictional, this scenario isn’t farfetched. Many rural communities occupy areas rich in biodiversity and mineral resources, but are themselves short on capital and institutional planning capacity.

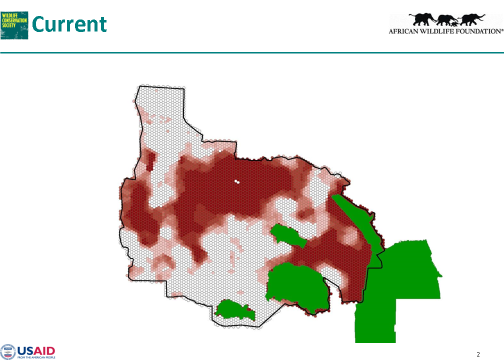

Red areas represent Marxan solutions for meeting habitat needs of suite of conservation targets under current climate.

Based on years of experience in the landscape, Nelson has an understanding of how individual portions of the landscape are used by stakeholders and contribute to maintaining the diversity of species and ecosystems. The montane forest provides a source of freshwater, habitat for wildlife, non-timber forest products, and nature tourism; the small plots of farmland propping up modest households with extra income and sustenance, while the vast grasslands both fatten cattle and support iconic wildlife. But what to make of the oil discovery and potential windfall of revenues, infrastructure development, and land speculation skyrocketing? Change can bring significant benefits to some but not without consequences both socially and ecologically. Many of the negative consequences can be avoided, however, if the development is well-planned, through a structured and inclusive decision process.

In this age of hyper globalization, rapid industrialization, and climate change it is not an option to make land-use decisions in isolation, particularly on land and its attributes as a finite resource. Yet it is no easy task to lay all the cards on the table and readily pick a path best for all. This is why a systematic and objective based approach is critical to making informed decisions about the future of the landscape. It becomes imperative to invite all the actors to the table and set objectives, values and conditions for solutions. A ship cannot build and haul its cargo by itself, likewise, ensuring thriving human and ecological communities, requires coordinated planning that considers the interlinked facets of the system and explicitly acknowledges the trade-offs involved in decision making.

Marxan is one tool in a shop of potential options for organizing several aspects of Nelson’s complex challenge, including where development should be encouraged and what areas are critical to conserve. Marxan helps Nelson elucidate trade-offs required between stakeholders, and navigate those trade-offs to help actors identify acceptable tradeoffs and outcomes. Marxan is a spatial optimization tool, not to be confused with a land change modeling tool, that aides decision makers in spatially allocating resources or prioritizing locations for conservation or development given an explicit set of objectives, eg. conserve 50% of wetlands while minimizing opportunity cost to pastoralists. Marxan works by aggregating spatial information on the values and activities that are important to stakeholders, including species, ecosystems, mineral resources and water. Then using stakeholder specified objectives it identifies alternative landscape configurations that achieve those objectives and can be mapped out and presented to stakeholders to promote thoughtful discussion and facilitate informed and efficient decision making.

On 19–20th June, ABCG partners, the African Wildlife Foundation (AWF) and Widlife Conservation Society (WCS) held a second Marxan learning workshop at AWF headquarters in Nairobi to review findings of a systematic conservation planning analysis using Maxan in the Kilimanjaro-Amboseli landscape of Kenya and Tanzania. David Williams AWF’s Program Director for Conservation Geography kicked off the event by presenting recently collected and synthesized data on wildlife distribution and related threats that served as inputs for the Marxan-generated scenarios. Participants were then briefed on of the guiding principles of systematic conservation planning, including the fundamental importance of setting quantifiable objectives upon which conservation progress can be measured within a transparent and accountable process. Dan Segan, Conservation Planner, Climate Adaptation Team at WCS, facilitated the review of how the Marxan methodology, based on those fundamental principles, was applied in the Kilimanjaro-Amboseli landscape. The workshop guided participants through how the information was incorporated into the landscape analysis and how the results of the analysis can be used to highlight critical conservation focus areas.

Lucy Waruingi, African Conservation Centre.

The workshop also:

- developed landscape storylines constructed around desired outcomes across specific themes (e.g., water resources, wildlife species, land uses)

- discussed a communication strategy involving development of communication materials and storylines tailored to individual audiences such as policy makers and land use sector leaders.

Workshop participants included representatives from the Kenya Wildlife Service, the Tanzania Wildlife Research Institute, AWF Landscapes staff, the School for Field Studies, African Conservation Centre and the Geological Society of Kenya. Many participants offered valuable expertise and feedback on the Marxan generated scenarios, including target suitability, gaps in scenarios and data, and much more. Furthermore, participants identified new opportunities for action such as additional wildlife species that could be added to the analysis to strengthen future Marxan scenarios.

Participants also discussed barriers to change, and how to best communicate findings of the work and engage stakeholders to move the project forward with constructive input, and benefit land and resource managers such as Nelson.

aarp approved canadian online pharmacies

canadian rx pharmacy